Welcome back! This month we’re taking a full on dive into Science Fiction written by Women, because while it won’t shock any of the no doubt wise and worldly readers of goonhammer dot com, there are plenty of people out there who still think that to write good scifi, you’ve got to be all four of white, balding, glasses, guy.

So this month we’re going to look at three Feminist SF classics – not just Science Fiction written by women, but Science Fiction deliberately written to explore feminist themes. If you’ve just rolled your eyes and you’re about to close the tab, good – fuck off.

[Condit Editor’s Note: The views expressed by Lenoon in this paragraph are entirely his own, but coincidentally also represent the views of the editorial staff. If you don’t like it, eat shit]

Women’s writing is not only vitally important to the history of Scifi, but has its own, unjustly maligned sub-genre – Feminist Scifi. This is writing on explicitly feminist issues, exploring broadly what it means to be human through the lens of SF, but also the place of womanhood in this context. It’s more than a little unfair of me – and everyone else – to shuffle explicitly feminist SF off into its own subgenre, especially when putting SF written by women into another category of book – often Young Adult, or even *shudder* General Fiction instead of in SF where it belongs – is an unsubtle way to denigrate women’s writing or separate it out of the boys club nerdom used to be. In lots of cases the difference between Scifi and YA Scifi is that the “adult” version is the same book but written by a bloke. Female SF authors all too often get a pink chair or a woodcut style slapped on their covers and shoved in with fiction instead of the mindbending art and place in the SF greats they deserve. Even labelling an author a “feminist SF author” gets them shuffled off into a corner where idiots feel they can ignore the fact that these books are extremely fucking good SF. It’s almost as if there’s some kind of entrenched power structure looking to subjugate women’s writing.

Feminist Scifi has a different perspective and purpose to excellent Scifi that is written by women – I’ve featured at least one female author in each article of this series, but few of them have been explicitly feminist. I can’t tell you what it should mean to be a woman – and god, I’d be one of those complete pillocks you see on twitter if I tried – but reading Feminist scifi gives male nerds (like me, and maybe like you) a place to listen, learn and evolve through the familiar space of the future. SF is about taking what’s familiar to us (human experience) into an unfamiliar place (the future) and, in doing so, exploring more about the familiar, shining a new light on it and exploring it in a new way. This month we’re flipping that script – let’s take what most readers of goonhammer articles are familiar with – visions of the future – and learn something about a reality I, at least, am deeply unfamiliar with – the lived experience and reality of being a woman.

Feminist Scifi does everything that not-explicitly-feminist Scifi does, but does so through being rooted in female experiences. The horror, the wonder, the character development, all comes from and through a different perspective to nearly everything else you might have read. A friend of mine clarified this for me a long time ago – When the horror of Alien is fundamentally “you can be unwillingly impregnated by this particular monster and there’s one loose on the spaceship”, how horrifying must it be to think that it’s not one monster, it’s potentially half the crew? That’s what we’re thinking about here – Scifi, through a lens you might not usually look through.

What is Feminist SF?

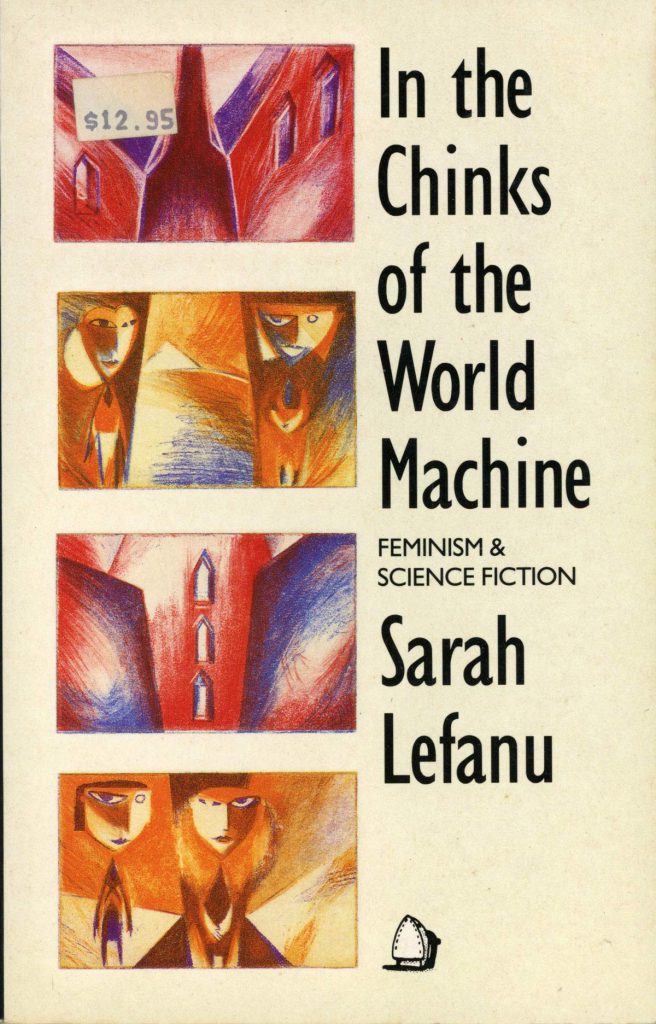

One of the series we’re exploring in this series is the now defunct Women’s Press Science Fiction imprint. This ran for around a decade in the late 80s to early 90s, republishing unfairly lost or forgotten masterpieces of SF, providing new and established authors a space to publish works that the big name publishers – like our other series publishers Gollancz and Penguin – were at the time unwilling to print, and exploring just what feminist science fiction could look like. A lot of it is angry (and rightly so), a lot of it is queer and a lot of it is experimental. It’s a series mostly written for and in a very specific context and as a window into the 80s and 90s on both sides of the pond, it’s an incredible historical artefact. To a veteran of reading classic SF, it’s an interesting collection. There are big, giant, impossibly huge figures (Jo Russ), authors whose work might be more-or-less lost to history if it hadn’t been for people deliberately forcing republication (Perkins-Gilman) and some incredible late 80s British and US pieces where the authors never got the recognition they deserved (Elizabeth Baines’ The Birth Machine is one of the purest horror SF concept novels you’ll ever read). There’s also a fair bit of strange, challenging, experimental and downright weird stuff. It’s not always 100% knock it out the park amazing SF, but its always worth reading. It’s telling that 40 years on from publication by the Women’s Press an ever-increasing number of these are appearing in the Gollancz list, and it’s about damn time too.

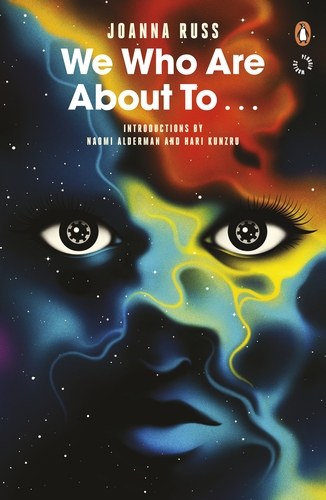

Joanna Russ – We Who Are About To

Content Warning: sexual violence

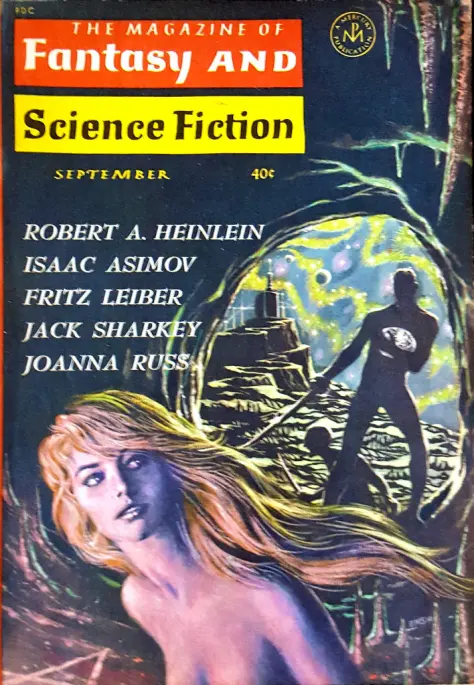

Joanna Russ is the greatest Scifi author you might not have heard of. I’ve mentioned her name repeatedly through this series, and to me it is absolutely unquestionable that she’s up there with the absolute greats of the Scifi world. She was a phenomenally prolific writer of both science fiction and an incredibly important work of literary criticism – How to Suppress Women’s Writing. She wrote angrily and rightly bloody so – it sears through her writing and her work is science fiction filtered through unrelenting, justifiable, urgent rage that makes everything she wrote incredibly powerful. On top of that you have satire, humour, hard Scifi concepts, well realised characters and beautifully paced, smooth writing. Russ really, really knew Scifi and how it worked. She understood how to write good scifi and how to write a sarcastic review of shovelware crap, something the authors of said shovelware really fucking hated. She’s angry, and she’s never, ever, boring, or predictable, or staid.

Working out which one book to recommend is hard – The Female Man is always extremely popular, Picnic on Paradise is fantastic, Souls is great and a worthy Hugo Winner, The Two of Them is a rollicking space adventure, but We Who Are About To... is just, well. It’s perfect.

We Who Are About to… is a short novel that addresses the standard SF trope of “humans stranded on a planet” with Russ’ exceptional spiky rage. When Science Fiction strands set of astronauts on a planet, masculinist exceptionalism tends to take over – we’ll repopulate the planet! We’ll start our own society! We’ll breed a new race of humans! – without, ever, asking what the women might want. Russ asks and answers those questions. What if a woman doesn’t want to be the brood mare for some complete prick’s new utopia? What if, instead of fading into the background as a cipher for a male story of survival, what if you didn’t write Earth Abides, but you wrote something more real, more important? What if, instead of a brave new world being born through rape, a woman had agency and peacefully refused? What if, then, the colonists tracked her down and demanded she give up that agency so that the men could live out their sexual-assault based new world order? She’d kill the fucking lot of them.

We Who Are About to… is a strong, beautiful and sad book that delves deeply into isolation, loneliness and the experience of living in a society that attempts complete female subjugation. It doesn’t go down the route of seeing that society realised though, because it’s smothered out of life by female agency, a story of resistance and strength that (male) reviewers goddamn hated, but has more recently been recognised as one of the pinnacles of Scifi writing.

Ursula LeGuin – Left Hand of Darkness

You know, I was going to save everything from LeGuin for her own article, but that meant deliberately not writing about one of the top Scifi authors, which is just crazy, right? LeGuin is such a ubiquitous name that you’ll know her work already – Earthsea maybe, or the archetypical early 70s SF that is Lathe of Heaven, or the wonderful anarchist manifesto in the shape of a novel The Dispossessed. It’s bloody difficult to talk about Le Guin’s influence on Science Fiction because it’s arguable that with the exception of PKD she was the most influential author in the genre. She was an anthropologist, a literary critic, a damn good author, a guiding light that shows what Science Fiction can do – what it should do – when it’s less obsessed with the mechanics of how faster than light drives work and more concerned with what it means to live in a society in her fascinating, intricate worlds.

The recommend is the first novel written by a woman that won both the Hugo and the Nebula awards which would make it a landmark in feminist SF anyway, in addition to the fact that it’s an exploration of gender, relationships, friendship and politics. Left Hand of Darkness is part of the Hainish Cycle, but is most definitely standalone. When Ekumen envoy Genly Ai is sent to Gethen to liase with the political elite, he’s thrown into a unique and confusing situation that he can’t wrap his head around – an ambisexual planet where individuals move between sexes, creating an androgynous culture that denies many of his baked-in terran assumptions.

Genly is shuffled through the politics of Gethen with the aid and occasional hindrance of Estraven, prime minister of the kingdom of Karhide. Genly and Estraven develop a complex and real relationship, culminating in the greatest single set-piece in SF history, an arctic hike across a frozen desert that cements their relationship in a phenomenal bit of writing. Le Guin uses the gender ambiguity of Estraven in contrast to the “known” culture of earth to explore what it means to be gendered and agendered, to engage with different understandings of gender and to open up both narrative and emotional possibilities.

Left Hand really ignited the first pronoun argument in Science Fiction – that the use of masculine pronouns for the agendered people of Gethen didn’t support the core thesis of the novel – and furthermore that the “feminine” characters of the novel are usually seen in domestic contexts and furthermore that both core characters are masculine coded and never physically express their attraction. All of these points are, in my opinion, very true – Le Guin reflected in an anniversary edition that many of them were mistakes. I’d have loved to see an edition come out in her lifetime that changed the pronouns. It’s not a flat out critique of masculinity as a result, much more subtle than We Who Are About To, but perhaps that’s what has “allowed” the very male dominated SF world to acknowledge Left Hand as a true classic.

Suzette Haden Elgin – Native Tongue

While the last two recommends have been fairly high concept, Native Tongue takes us firmly into Hard Scifi concept-driven excellence. Suzette Haden Elgin is famous in a very certain section of the Scifi world, particularly wherever an author is playing with Linguistics, the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis that language programmes our brains to think and act in a certain way, or working out the details of an alien language and culture. Haden Elgin was a writer, poet and linguist, and her best known work is the Laadan cycle (though definitely check out her work with the Science Fiction Poetry Association). Here, a series of novels with a slight unfortunate diminishing-returns-in-sequels vibe deals with interstellar translation, feminist resistance and creativity, focusing around the concept that Languages structure thought and action. It’s what noted Black Library author Ian Watson edged towards in The Embedding, but taken to a fantastic extreme and told through women’s voices and a women’s language.

Native Tongue takes place long after the repeal of the 19th amendment, and women are, once again, chattel property of their male relatives. This is an interstellar trading society, where vast wealth can roll into Earth and its strongly stratified society – but only when filtered through the linguistic skills of the translator guilds. There, men and women work to understand new languages, create new methods of translation and open up the galaxy to humanity. The men reap the rewards – and manage the tensions – of their strange clannish environment, but the women do the mass work of translation on top of training the next generation, running their fortress-like translator towns and putting the old men out to pasture.

When women are no longer useful, they’re moved to the Barren House. There, the women of the translator guilds are building their own language, one that aims to restructure their society and reprogram the human mind. We dip in and out of Men’s and Women’s cultures – the book has fun with men outside of the translator guilds constantly fucking up idioms and speaking in weird, stilted and cliched ways – before focusing in on two stories of personal freedom and rebellion and setting them loose within a carefully constructed world. There’s some fantastic little bits of high/hard concept SF in the translations and memorable and enjoyable characters interacting, and the lingering thread that you piece together as the main character does is an enjoyable detective story at the heart of the novel.

Language as both resistance and weapon is something that Haden Elgin tried to bring into the real world, constructing Ladaan, the women’s language, in real life. Not just as a curiosity or something to give structure to a story, unlike say, Klingon or Dwarvish (Elvish gets a pass as being more significant than this because I like hearing it), but as a real, alternative and potentially viable language that allows women to escape patriarchal grammar and linguistic structures. Maybe, just maybe, it could change how we think about the world if we could easily express everything we feel without deliberate ambiguity. Maybe, if we could make language itself egalitarian, what would we create? While the book doesn’t quite come together when it could – there’s a great climactic point that doesn’t sync up with the end of the book – and the sequels (Judas Rose and Earthsong are both ok) aren’t up to Native Tongue, this is truly visionary Scifi. What if we wrote books with the aim to change the world? Why don’t we?

Black Library Pick

It was bloody hard to find a Black Library pick on today’s theme. There’s an argument that being tie in genre fiction, the Black Library “shouldn’t be political”, but, as we know, this is code for “shouldn’t include politics I don’t agree with”, or at the very least the themes shouldn’t explore anything other than universalist ideas or life through a masculine lens (the soldier, the warrior, the horror of war but only rarely from a civilian perspective). Black Library writing, like all writing, is of course political – it just doesn’t always appear to be. Today’s Black Library pick explores what it means to be human, and female, in the 41st millennium.

Danie Ware – The Rose at War

Nuns are a very particular type of female experience and though there’s a lot of Adepta Sororitas fiction out there, the others don’t quite get the quintessential nun-ness across like Ware does. Ware’s Sororitas are always singing. They are always faithful. They are friends – sisters, not brothers – they are not Space Marines and aren’t written as a gender swapped version of them. They kick ass in their way, wading through Orks, Heretics, Genestealers and everything the universe can throw at them. They feel fear and overcome it. They exist as fully fleshed out characters rather than as one-dimensional ciphers of one of the few “female warrior” archetypes present in the 40k universe. Rose at War puts the last pieces together of the 2019 relaunch, firmly killing the wink-wink 90’s studded corsets and nuns-with-guns vibe and making those elements parts of something much more meaningful and ultimately something much more interesting.

This is women at the forefront both of the fiction and the grimdark wars of the far future. Strong, capable, complex characters expressing a particular lived experience of gender and the hell-scape of the 41st millennium. As someone taught by Nuns at various points, the chilling grimdark reality of the Sisters at War is different by degree only to chilling grimdark Catholicism, making it a pretty interesting way of exploring a particular female experience in the 41st millennium. Just like the above examples where the novels are saying something important in addition to being great SF, Ware also really fucking gets 40k writing. It’s bombastic, it’s bloody, it’s borderline insane in a universe drenched in madness.

Not only should you pick this up you should also check out this fantastic interview on Track of Words that touches on what it’s like working for the Black Library – and the experience of being the one “offered the ‘strong female character’ options, even when it’s not Sisters fiction”. I really want to read more Danie Ware stories, and I think you will too.

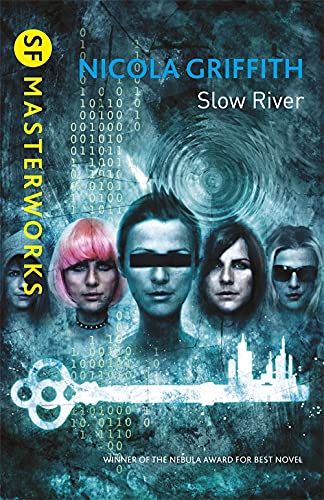

Slow River – Nicola Griffith

Slow River is another book of a decaying, brutal society in which female friendships – and in this case love – forms a path through the endless drizzle of a cyberpunk future for the protagonists. I was really put off Slow River when it first appeared in my bookshelves, because it’s been given a number of “general fiction” covers that undersell the spikey, gritty and gripping cyberpunk novel within them. I like writing this for an audience more likely to pick up a book with a scifi cover than the dreary one it’s saddled with in too many bookshelves. Now in the SF masterworks where it firmly belongs, it has a fantastic cover that’s worthy of it’s content and, being a shallow bastard at heart, that finally got me to pick it up.

And oh man is it worth it. Slow River is a classic piece of cyberpunk-adjacent writing that’s full of the gritty darkness of the near future, and full of the tiny moments of love, care and detail that fill up your life. It’s a wonderfully written novel that delves into environmental (and sewage) science in surprising detail, building up a really rich picture of another world that’s just out of reach. If nothing ages faster than the visions of the future, Slow River is surprisingly (now 30 years on) still a realistic idea of the future, in addition to being fantastical and wide enough to create a world that’s all about weird internet scams, aphrodisiac mind bending drugs, nanotech and geoengineering on a planetary scale. Then it’s also about love and lesbianism and working conditions in industrial labour and a detective story. It’s all about tiny little details of human life and interaction and what makes us who we are. Finally, it’s a really brutal cyberpunk story with (almost) everything that entails. Whatever it is, it’s goddamn great and its that mix of human detail and excellent grit that makes it this months out of the Black Library read.

Nicola Griffith has a great website that’s well worth checking out where she goes into detail on her writing process over several of her novels – Ammonite is another modern Scifi Classic that now I’ve mentioned it I’m definitely going to reread immediately, while Hild is great historical writing. Spear is on my wishlist. Reading her blog is well worth your time.

Questions? Comments? Suggestions? Genuinely upset that I didn’t mention Sheri Tepper and Gate to Women’s Country, or Grass, despite my noted hatred for horses? Get in touch contact@goonhammer.com, or leave a comment below and join our Patreon and talk about books, please!