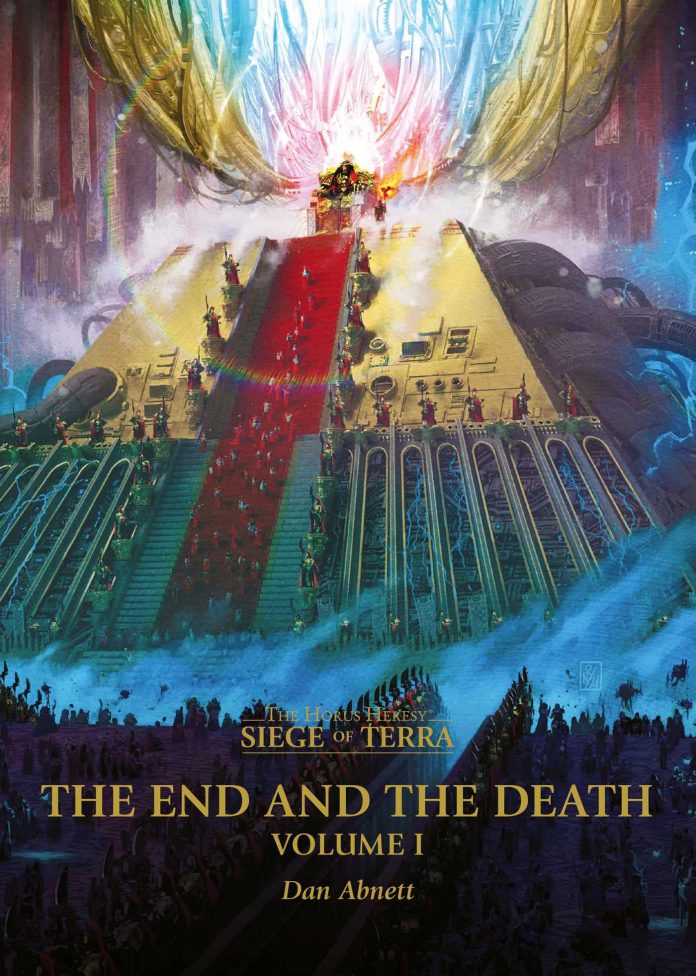

So it has come to this. The Emperor is off to fight Horus. We have reached the End and the Death.

How we think this story should end is not just from the Siege of Terra, or the impossibly lengthy Horus Heresy series. It comes from 40 years of background lore in a dozen different sources. It’s in a thousand different tabletop skirmishes, a mass collective creation of expectation, built by untold millions of tumbling dice. Many of us had this conversation in schoolyards – how will the final battle go? – and now, decades later, have it again, sometimes with the same people, in game stores – how will the final battle go and how’s that back trouble doing? Our shared experience amounts to an incomprehensible tangle of stories and hopes, and now, somehow, Dan Abnett has to bring it to an end. When the author and name of the final book was announced, was it a surprise? Abnett must write the End and the Death. Noone else could. Now we’ll see how he finishes it.

The End and the Death is a fine Black Library novel, a worthy end to a saga of impossible length and mind-bending complexity. It has fighting, secrets, chaos and horror. It has catharsis and triumph and tries nobly to tie everything we’ve seen so far together. You’re probably going to read it, if you’re here, whether now or in months or years time if you’re still working through the Heresy. It isn’t, however, all that we could have hoped for.

We’re not going to go into every little detail of the plot here. I can’t promise this will be spoiler free, but we’ll give it a go.

Warning: This review contains (very) mild spoilers for the end and the death

The Death

Working out the story he wanted to tell must have been the most difficult part of writing this for Dan Abnett, because we know what should be in this book and can even guess what should be in part two – the shields of Horus’ flagship are lowered, the Emperor, Dorn, Sanguinius and his Custodian Guard teleport aboard. A fight ensures.

So the simple summary of the plot of the End and the Death is just that. That’s where the book ends, with the major players drawn to the Vengeful Spirit where the final drama will unfold in part two. We’re not quite at the End or the Death, as a result. We’re taken through the final dying days of the Siege of Terra, where the Loyalist forces are either locked behind the Eternity Gate or they’re ending their lives in blood and pain out in the ruins of the Palace. The last remaining figures of the Heresy are drawn together to play these final moments out and their stories intercut at a rapid pace to draw both the broad strokes of the end and a thousand very personal, often extremely terminal, details.

What makes the End and the Death worth reading is in those details. Elements of the story that are 30 years old, or came out of the Collected Visions and the rest of the Heresy are brought to life, fleshed out – given context and shape and sense that they’ve always lacked. We’re left knowing much of the why of the familiar story when we’ve only had some of the what before. When that happens, it’s rarely in the way you expect and Abnett subverts, expands, surprises with foreshadowing or provides new – and better – explanations of exactly what’s going on as the final gambits play out. There is new information here, exciting, gripping, lore with massive implications radiating backwards into the Heresy and forwards into 40k. That’s one hell of an achievement because while the plot summary of what was expected to be in this book is two lines long, the book itself is much, much longer and deserves (nearly) every one of those pages.

The core plot thread certainly earn their significant length. Two overarching, multi-character narratives of Order and Chaos add strength, compulsive reading and gripping revelations to the novel that make for a satisfying division between climax and denouement. The Order strand gathers together the biggest players of the Loyalist side of the Heresy – the Sigilitte, Emperor, Primachs, and Valdor – into the speartip thrust that will decide the Siege once and for all. They’ve rarely all stood and interacted in a single space, and the sections describing their journey to the Emperor and the decisions made in his presence are compelling stuff that capitalizes on the years of build up to the moment the plan comes together. The other major strand is the chaos – the literal state of the warp – that has built on Terra. Our world is now stuck in an endless moment, the doomsday clock set firmly at one minute to midnight. Here, Abnett gets the chance to play with the manifestations and effects of chaos through the eyes of both loyalists and traitors, generating some seriously spine-chilling horror, action and the mental and physical degreation of chaos. The situation in the last hours is simultaneously confused and confusing, characters and plots stuck in an endless loop of death and murder that they seem powerless to escape or effect. The mental and physical state of the loyalists is explored well – everyone exhausted beyond reason, everyone summoning up one last effort as the neverborn proliferate across the surface of the earth and the final positions are ground down to blood-stained stumps.

All of the best weird, interesting, questioning stuff, the most enthralling background work and early revelations reaches a fever pitch as the Sigilitte/Emperor hands over the major plot work to the warp-drenched chaos. When the last-chance play is made, we get chilling horror (Dorn gets one of the best bleak horror sections the BL has put out), the terrifying majesty of the emperor, convoluted gothic description breathing insane life into the world and some good old fashioned rooty-tooty-point-and-shooty, all set in the seconds after the teleport flare dies away. It’s great, gripping stuff and the high point of the whole of End and the Death. Unfortunately, it happens right in the middle of the book.

Cutting Threads

The chaos of the siege doesn’t help the second half of the book. Everyone’s had an approach to the immense scale of these final hours in one way or another – the Solar War added literal space to numbers, Saturnine slammed through hundreds of overlapping viewpoints at a rapid pace, Echoes nailed the conflict to a single, burning point. The End and the Death attempts to do it all, and for all of the skill on show in writing different voices and perspectives, it’s where the novel creaks and breaks. We’re told rather than shown the preposterous scale of the conflict. It feels less apocalyptic and terrifying than the masterwork that was Saturnine because it loses the key focal point to show the desperation we’re told is present. Chapters of “Fragments” – single paragraph or even single line vignettes – are supposed to show us the full extent of the siege, and sometimes do this to great effect. Others, unfortunately read like some of the early attempts to establish the Stormcast Eternals as viable protagonists, all nounverbers at the placenames against the adjective verbnouners. There’s just too much context. We know the world is on fire, but seeing every single flame detracts from the inferno.

This also applies to larger and more important, but still peripheral, stories. Abnett is put to the task, as he was in Unremembered Empire of pulling all the myriad storylines together, and End and the Death suffers in the same way that the beginning of Imperium Secundus did. There are many side stories here that come together gradually, or separate, or find themselves moved towards resolution as the book goes on, but for a long, often frustrating time, they’re left dangling. It’s a conclusion book and a setup for the presumed Scouring series, and of course only part one, but the many trailing threads leave sections of the book without a focus. Every now and again there’s a round trip to check on the moving pieces, but there’s too many to leave them all important or useful. Those checkups aren’t as satisfying as they could be and occasionally seem to be missing sections from previous books – Keeler lacks the edge that Wraight had used to chilling effect in Warhawk, the Perpetual Gang are always, as they have for the last 15 years, on the edge of doing something interesting but never quite managing to be interesting, Rann and Zephon are sent to deliver the bolter-porn chapters that feel curiously out of place, as if mandated to shift sets of character models and the Dark Angels do Dark Angel bullshit here, of all places and all times. This isn’t to say the book doesn’t come together, but that the focus has become too large, and there are too many stories that have to come together when it would be a better book to leave some to the imagination. It simply does not matter what 99% of the dramatis personae in this book do, because it’s not their story, for all that they appear in it.

Checking References

As the fragments proliferate, we’re also assailed with references. So, so much of this book is spent referring to things in the grand and tiring style of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. There’s so much that clearly needs to be referenced, or name-checked, or brought in as a significant subplot, or foreshadowed for 40k or just flat-out enunciated, sometimes repeatedly, until you get the point. There are chapters that seem designed around nothing else, once or twice to a groan-worthy extent. There’s a million literary, historical, GW and Heresy references in there to the point that some of it is just winks and nods, and eventually the story, blissfully, drags itself out of them.

Despite all that, some references build significant, creeping and horrible tension. By having the resources of the mega-series and the 40k universe to draw on, occasional and cleverly chosen nods and fleeting mentions build to a final apocalyptic revelation with a good bait and switch you’re prepared for – and wrongfooted by – from the beginning. There, the dripping tap of tiny moments and disconnected vignettes build to a satisfying, purposeful moment where the full horror of Chaos is revealed. Reference after reference build, almost subconciously, to a 40k-universe-shattering revelation, one that will draw a million points of speculation and theorycrafting far into the future. The chapters choking on nods and winks do have a point – and the point is more terrifying and important than you can imagine. It’s the kind of thing that the Black Library only allows Abnett to do, hinting at the nature of the universe to such a game changing extent that it must have been planned out alongside the Bequin series. Perhaps the point of all the other references was to distract, so that when the curtain drops and the twisting narrative briefly straightens, we were busy thinking about Alexander the Great, Eigyr Pendragon or Jesus.

Horus Rising

Focusing in on one character pulls us up and out of a morass of tiny stories, and that’s best done with the big man himself. It’s the Horus Heresy after all, and now as we reach the very end, we get some of the best Horus stuff in the whole thing. Now, when so little time remains, we see Horus anew. We see Horus through various eyes, and most interestingly we see him as he sees himself in first and second person passages that convey the Horus that was, is and threatens to be. The first person sections are tragic stuff, Horus the bright and arrogant discussing his ascension to Warmaster, a sad and somewhat sinister reminder of what could have been and the story Abnett started with all the way back in April 2006. Then, with his habitual gift for pacing and twisting a narrative, Abnett slams us into Horus’s head in the second person.

Second person is pretty rare in Warhammer fiction, one of the best examples up until now a decent crack at horror in Anathemas, and it’s startling to be firmly wedged behind the eyes of Horus after his open and friendly dialogue with you as the reader in preceding chapters. Horus as he presents himself to Mersadie Oliton gives us the man himself in his own eyes, in stark contrast to the second person sections where we as the reader are chained to a broken, demon-haunted husk of arrogance, hubris and madness. Horus has ascended, confusingly and terrifyingly, and these sections are amongst the best and most interesting of the book. They lay the groundwork for the big revelations, they drive the plot forward and they allow Abnett to draw up Horus as a worthy enemy of the Emperor.

A lot of that is done through a cultural code-shift for the traitors which runs throughout the book but is strongest and most immediately evident in the Horus first/second person chapters. The Legions – Emperor, Custodian and Astartes are directly linked to a variety of figures of classical myth and history and god they don’t half talk about it. There are rare breaks in this characterisation that Abnett employs to switch tone – the courtly Dark Angels and the disgustingly medicalised Death Guard (and the Lovecraftian vibe when the two collide) and his tiny dip back into the world of the Rout, but overwhelmingly the Loyalists are and have always been, classically inspired. They are full of empire, structure, law, battle and order. Horus and the Traitors dwell in other sources, older “pagan” references and modes of speaking that reflect the deep influence of Moorcock on the whole idea of Chaos. Horus speaks like a Warlord, not an Emperor, particularly when dealing with the metaphysical world of the Gods and Demons. There are sections where he could be reading straight from the Mabinogion, drawing on rich cultural memories of saga and fireside-spun tales. Demons are named and tallied like the thirteen great treasures of Britain, or the tasks of Culhwch. At one point Horus visibly displays his father-given ring, the mark of a long martial history stretching back around the edges of the empire to Beowulf and before. It’s one of the ways Abnett hammers home the Gibbon reference – we’ve had much of the Decline of the Roman Empire, now comes the fall.

Imperial Gothic

Some of that obsession with the influence of the past, and the fall of Rome particularly comes out of Abnett’s recent literary playground of Gothic fiction. 40k has always been pretty gothic and it’s appropriate that as the bright, sunny 30k world chokes on hubris and promethium, we’re transitioning in form into full blown Walpole and Shelley gothic. It’s clear that Abnett goddamn loves writing a gothic novel when armed with a victorian thesaurus. He revels in the genre to a luxurious and occasionally gloriously preposterous extent, particularly in the Malcador sections where the Sigillite-as-author-proxy takes great pains to speak, act, think and describe in high gothic style.

Everything you’d expect from Gothic literature is here; lingering sensual description, inexplicable death, melancholy and sickness, realism and horror, the past intruding on the present, fake-historical documents interleaved with prose sections, weather, comparisons of XY and Z to falling leaves, moral, physical, and architectural ruin, deep introspection, a preoccupation with pathetic fallacy that works because the warp really does infect everything with a creeping anthropomorphism, and more hypallage than the groaning page can contain. Then, in another place with another character, you’ve got all the chainsword and bolter action you expect. It’s often used powerfully to break up the rhythm of chapters and sections, thrusting you forcefully from warzone to dungeon and back, and it makes 30k a richer and weirder place even as it dies.

There are readers who will have – and always have had – a deep and visceral dislike of the Black Library when it experiments away from flat description of character intent and the smack of bolt rounds as they detonate. But personally I think it works. The Hinzerhaus of Only in Death and the strange, slow melancholy of Pariah and Penitent are building blocks that lead to the End and the Death as much as the stories of Loken and Keeler do. As a reading experience these sections are hypnotic and cloying, conveying wonder and terror and insignificance, provided you’re into this kind of literary flex. As you can tell by the way I write, I am – the more semicolons and inappropriate verbiage the better.

Abnett Unbound

So that’s what’s in the book, what’s good about it, what isn’t so good, and how it’s written. But that’s not all this one is, because there’s a great deal of symbolic importance to the End above and beyond it being the first half of the End itself.

The End and the Death is the final, torturous step on the road the Great Crusade began. With the empire contracted to a single planet, the dream of the great work lying in ruins, the full fury of the Space Marines exhausted and turned inward to purge and scour the homeworld itself, you can’t help but see the beating heart of the novel as Dan Abnett. Not the Emperor, not Horus, not Malcador. Dan.

Abnett started this journey. He, more than anyone else, created this empire, breathing life into it with his craft, carrying the immense weight of the rapid and inexorable expansion of the Black Library on his shoulders. Others have carried the burden, taken it forward into amazing and interesting places, the sons reaching further and stranger than the literary father, but Dan created this. Dan set the Great Work of the Black Library – guided, of course, by publishers and editors – in progress. Dan, more than anyone, pushed GW’s publishing arm to a place where they could accidentally produce the longest single series of novels in the history of literature. The Daniverse of Alpharius, the Mournival, the Remembrancer Order, Promethium, Noospherics, lost Tanith, the Riders of the Dead, Enuncia Gaunt, Eisenhorn, Ravenor, Darkblade, Hekate, Ganz, Loken and Omegon, created the names and characters that began all this, and he has stepped forward to finish the job. The End and the Death can’t, and won’t, escape that role in our reality, and that means tying up dozens of authors stories, and 17 years of Dan’s own, no matter how long that takes or what it does to the book.

Because this is the end. It reads like a valediction or a eulogy for an era of the Black Library. There will be other books, from the Black Library and from Dan – this is only part one after all – and there will be other series. But none like this. Part Two won’t be the last Black Library book, but it sure feels like it could be. This one stumbles a little in the morass of stories, but we should remember the End is not quite here. Hopefully in part two, when the must-tie-up threads cease their infernal dangling, we’ll get the End and the Death.

Have nay questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com.